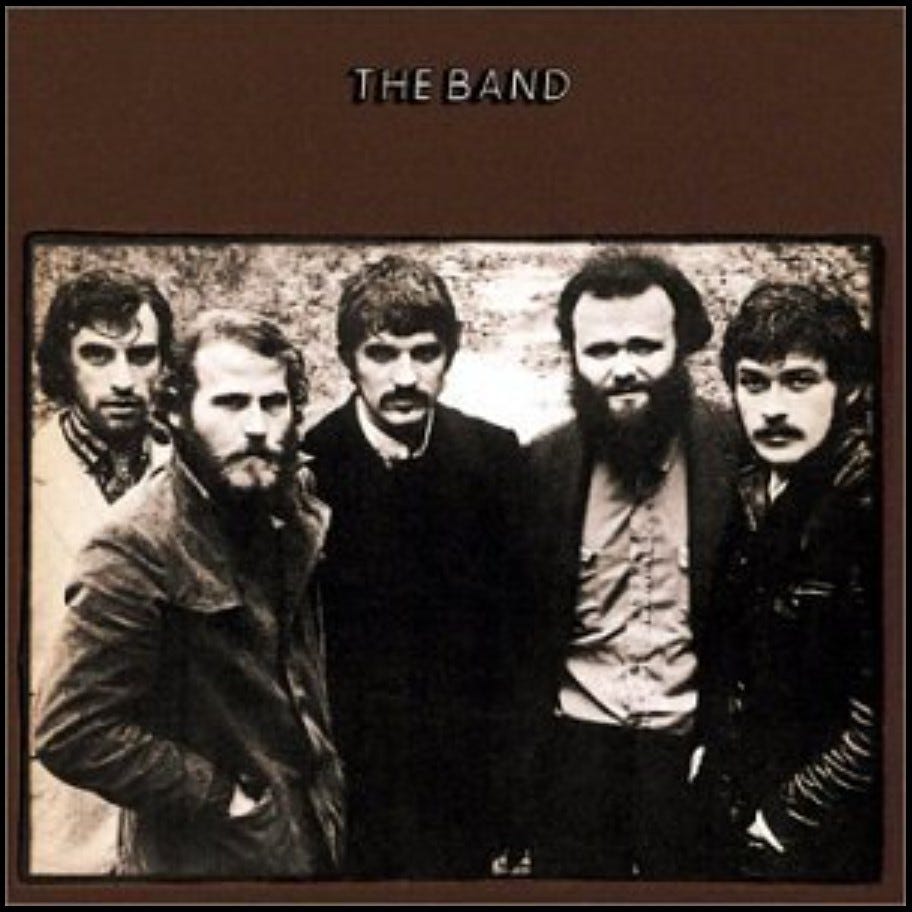

Track 5, Side 1: The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down by The Band

A haunting home visit and an all-timer show stopper

My dad taught me every epic journey deserves a great soundtrack. My PalliMed Mixtape is the story of my Palliative Medicine Fellowship year, told in 15 songs.

The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down in Apple Music

If you’ve never seen The Band’s concert film The last Waltz, please check it out on your favorite streaming service. It’s incredible. It’s directed by Martin Scorsese, for heaven’s sake.

If you don’t have 2 hours to watch a 45-year-old concert film, surely you can spare 4 minutes. Go over to youtube and watch the clip of The Band performing The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down and prepare to have your mind blown. It is my favorite filmed vocal performance of all time. Levon Helm is an absolute maniac, keeping it tight on the drums somehow while simultaneously singing with the passion and desperation of a starving rebel taking his last stand. The exaggerated pause at the end of each verse, the synchronized salvo of explosive harmonies on each chorus, even the fist pump from lead guitarist Robbie Robertson as the momentum builds…it’s everything you want from a band at the peak of their powers.

It’s also a great song to tell the story of a home visit that still haunts me.

Until this fellowship year, I had never cared for patients in their homes. What an adventure that has been! (And all this time I thought the ER was a raw experience!) I learn more about my patients’ lives in two minutes of seeing their homes than I could in a lifetime of clinic visits. I’ve learned I never know what I’m gonna get.

On home visits I get to pet dogs, touch quilts, study photos, and admire charming heirlooms that would fetch a mere few dollars in a garage sale, but that in these homes are priceless mementos. Just as often I get to bear witness to the mess, the filth, the foul smells, the poverty, and even the loneliness and despair. Regardless of whether I like what I find in a home, at least it’s honest, and it always helps me understand how to best care for a patient.

Now, I don’t mind chopping wood / And I don’t care if the money’s no good / You take what you need / And you leave the rest

Driving out to Jerry’s place west of town for a home visit was an ordeal. We wove along roads that progressively narrowed—paved, then gravel, then dirt—dodging dogs and loose livestock all along the way. Jerry’s friend met us and walked us down a path to the old aluminum shell of a trailer where Jerry was staying as he battled lung cancer. He had missed his most recent follow-up appointments.

I’ll be honest, I wasn’t too surprised to see an old confederate flag on the wall as I stepped into this sad, stuffy space. Confederate flags are still fairly common in small town Texas. Mixed in with the flag I saw some more artful tapestries, but the faded colors of Dixie still popped. Really, man? I thought. It’s 2023. Can you not take that flag down?

Like my father before me / I work the land / And like my brother before me / who took a rebel stand / he was just 18, proud and brave/ when a Yankee laid him in his grave

As my eyes further adjusted to the dark inside this hot trailer, I scanned the clutter and found jumbles of pill bottles scattered helter-skelter around the room, half-consumed bottles of Ensure, flies feasting on food that Jerry hadn’t touched. Then I saw Jerry himself, a specter lying in the dark, and his body revealed instant clues to the severity of his disease—his labored breathing, his gaunt features, the exaggerated convexity of his chest, each rib so distinct with no muscle or fat left to cover them. Sweat dripped off his pale body as he cried in pain.

We got him some of his pain medication and quickly made the decision to call 9-1-1. He clearly needed immediate attention and was not yet ready to embrace the finality of hospice at home. He was among the sickest patients I’ve ever seen outside of a hospital. I caught myself staring.

In the winter of ’65 / We were hungry, just barely alive

After some long moments I snapped myself out of my trance and forced my gaze away. As my eyes drifted up from their hypnotic fixation on his ribcage, I saw something equally as sick as Jerry’s lungs—a full-size swastika flag on the wall right above his bed.

I had missed it at first, but there it was. Crisp and clean. This was no historical artifact. This was a freshly made, recently purchased SS swastika flag. Now I started to feel sick.

Some still argue (albeit with less regularity and much less credulity than in the past) about what the Confederacy’s Stars and Bars may represent to white people in the South in 2023, but there’s no denying that a swastika represents hate, antisemitism, evil, and white supremacy. The ceiling of this nasty old trailer had just gotten a whole lot lower. I felt the walls closing in.

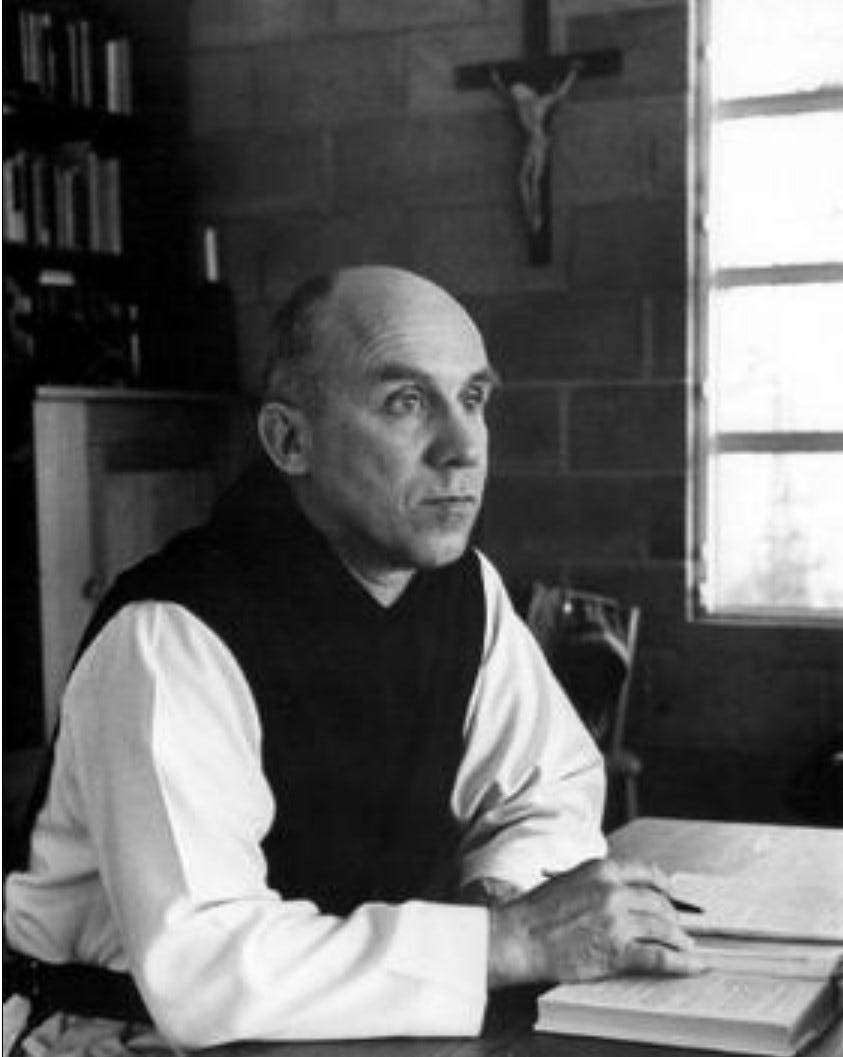

A question has echoed in my head ever since that day. How should I handle the tears of a Nazi? I had recently been reading some of the essays of the Trappist monk Thomas Merton who dealt regularly with questions like this.

(Photo of Thomas Merton: Wikipedia)

Merton wrote that, for him, empathy came from an understanding that his own faults and shortcomings were as great as anyone else’s. He believed that, deep down, he was capable of any of the monstrous depravities he saw in his society and in the world at large. To Merton, the fact that he had not traveled down certain dark paths was merely a reflection of God’s grace. He must therefore extend love to all persons.

Beyond that, Merton felt a responsibility to engage with the societal problems of his times. He didn’t like that he had to deal with the realities of Auschwitz, Hiroshima, and Vietnam—all of which happened during his lifetime—but he felt he had no choice. These were the times he was born into. He didn’t get a pass, and neither do I. I have to find my role in the midst of this messy society, and that can look different on different days. On that particular day, in my role as this man’s physician, it meant easing the pain of a neo-Nazi.

EMS arrived, and we escaped from this rectangle of sadness back into the bright central Texas sunlight. How should I handle the tears of a Nazi? As his physician, I should handle them the same way I handle the tears of anyone else. I should wipe them, and I should do my best to ease his pain. Even when I’d rather keep my distance.

Let’s finish this out with a little more Levon.

The night they drove old Dixie down / And the bells were ringing / The night they drove Old Dixie down / And the people were singing / They went, “Na, la la na la la…”

Tell me Crash Cart Campfire friends:

Does Thomas Merton’s call to empathy resonate?

What is your favorite video of a live music performance?

What’s on your mixtape?

That story slaps. What a banger. More deep than that hole Darth Maul falls into

"He believed that, deep down, he was capable of any of the monstrous depravities he saw in his society and in the world at large."

Such a lesson and insight there. Keeps the "us vs them" at bay. Plenty of historical examples and sociological studies that demonstrate this pretty well. We are all capable of what we find abhorrent. Many reasons for going down a path of destruction: mental illness, trauma that results in self medicating with drug use or destructive behavior, fall in with the wrong ideas in your community (Nazi Germany for a huge example, Rwanda). The banality of evil also comes to mind.