This story is from a while back. My unrefined prose does not do Mitch justice, but the people at The Examined Life Journal were kind enough to publish this effort last fall. I hope you enjoy!

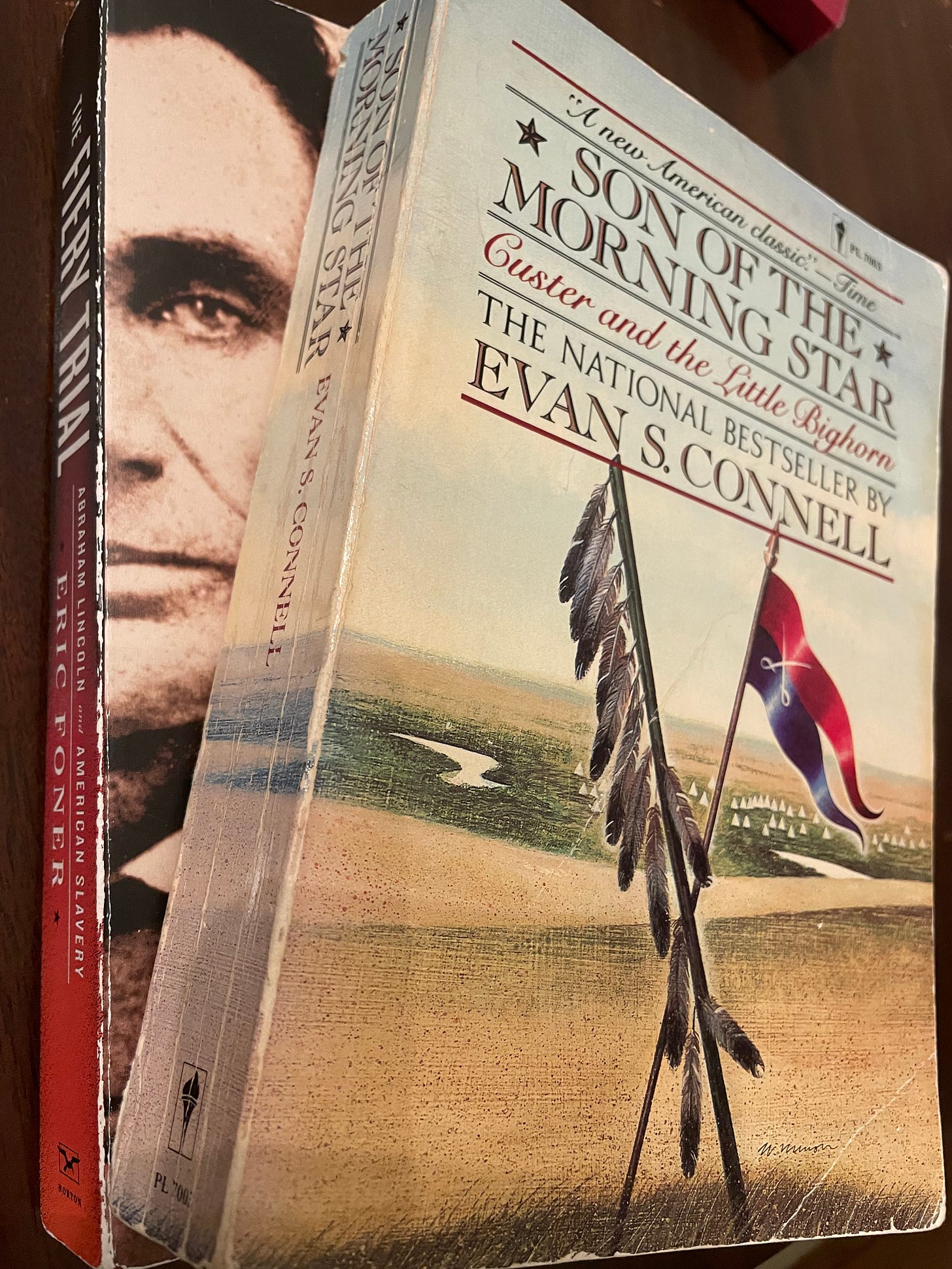

Mitch's paperback copy of The Fiery Trial anchors the stack of books on my bedside table. It's next to my hospital ID, my old wire-rim glasses, and a half empty cup of bitter, day-old coffee, placed far enough away so I won’t knock it over when I fumble for the light tomorrow morning. It waits there, underneath a Buffalo River paddling guide, Henri Nouwen's The Wounded Healer, and a book that promises to stop my physician burnout. It reminds me of my friend and brings a smile to my weary face.

I met Mitch on a Thursday evening in bed 17 of our emergency department. A thin, gray-haired, seventy-year-old New Yorker-turned-Texan, he reminded me of a kinder, gentler Alan Arkin. His advancing appendiceal tumor was now obstructing his GI tract, causing him pain and an inability to eat. As his ER doctor that night, I had a pretty simple job—order him some IV fluids and some pain meds, get him admitted to the hospital, and move on to the next patient. Finally, an easy case…and one without COVID.

It had already been a tough week. In addition to all the stressors of usual ER work, I faced tears, hugs, heartfelt goodbyes, and promises to stay in touch as my final shift at the hospital loomed. After seven years, I was leaving my medical family due to some hospital politics—a gut punch after a year in the trenches fighting COVID together. My heart sank heavier in my chest each day, but I just had to power through.

An hour or so after my initial encounter with Mitch, I was hustling around the ER to discharge a handful of chest pains and stomach bugs when I peaked back in his room to check on him. Mitch sat up in his bed, his thin frame looking oddly comfortable and relaxed. Even in his chemo and cancer-weakened state, the bowel obstruction didn't get him down. The crinkles around his eyes and at his hollow temples revealed an underlying smile that his baby blue mask couldn’t fully conceal. He was doing just fine, he said, didn't need anything, but just wished he could eat. As I stepped out of the room, he made a passing comment about books and American history, two of my favorite topics, but I didn't have time to chase the thought. There were COVIDs and car crashes that needed to be seen. Come back by at the end of the shift, I made a mental note.

When I wrapped up my workday around 9 p.m, a bit rattled but relieved to be done for the day, I swung by Mitch's room, exhaled, and sat down. Finally, stillness and quiet. No beeps, no alarms, no wails. I asked Mitch about himself. Though he had left New York after high school more than fifty years ago, his accent had never left him. He had a quick wit and a sharp sense of humor. "You know, I used to teach dawctas like you." He told me he had lived in Pueblo, Colorado and been a professor in social work, teaching medical residents for a while before joining the faculty at the University of Texas.

Mitch and I got to talking about books and found out we shared a love of American history and in particular the history of the American West. After a year of social distancing, isolation protocols, and constant gowning and masking up, talking with a history buff about books felt like coming home. After a while I needed to excuse myself. I hated to leave his bedside, I explained, and to miss meeting his wife, Adrienne, who would be here soon. But I needed to drive home, shower off all the COVID, and hug my family. I would visit Mitch again after work tomorrow.

Another hectic shift on Friday, but one patient helped slow me down. In her sixties, Debbie had been battling metastatic cancer for over a year. Her body looked incredibly gaunt; her muscle mass wasted. She needed relief from her abdominal pain and nausea, but the distension in her abdomen worried me as I began her workup. A CT scan revealed what I feared most—her small intestine had a perforation which would inevitably lead to sepsis. If a healthier patient had this diagnosis, she would get life-saving surgery. But Debbie, so weakened by chemo and cancer, had no chance to survive the operating room. This would be her fatal event.

"What's the news?" she asked when I came back into her room, her voice, permanently weakened by chemo and cancer, nearly inaudible behind her mask. Her quiet drew me in, as I had to lean head-to-head just to hear her. Sitting so close to her, I only had to whisper. It felt strangely and profoundly intimate. I held her hand and she took the news in stride, brave and resolved. "You are so strong, Debbie. How do you do it? How do you stay so positive? Thank you for the privilege of taking care of you today. I'll think of you and say a prayer for you when I leave this place tonight."

The insanity of the shift wound down, and I remembered it was time to go see Mitch. Nine o'clock on a Friday night. I braved the upper floors of the hospital and found his new room. "Oh, Dawcta! How nice of you to come by. You just missed Adrienne."

"Dang it, I'm sorry. How are you today?" I asked him, trying to get comfortable in a squeaky vinyl recliner.

"About the same. They won't let me eat because of this silly bowel obstruction." He paused, then grinned widely. "But they did bring by a book cart!” I noticed next to his frail body a stack of books on the bedside table. "Oh .yes…books are harpies. I just can't resist them, ya know?

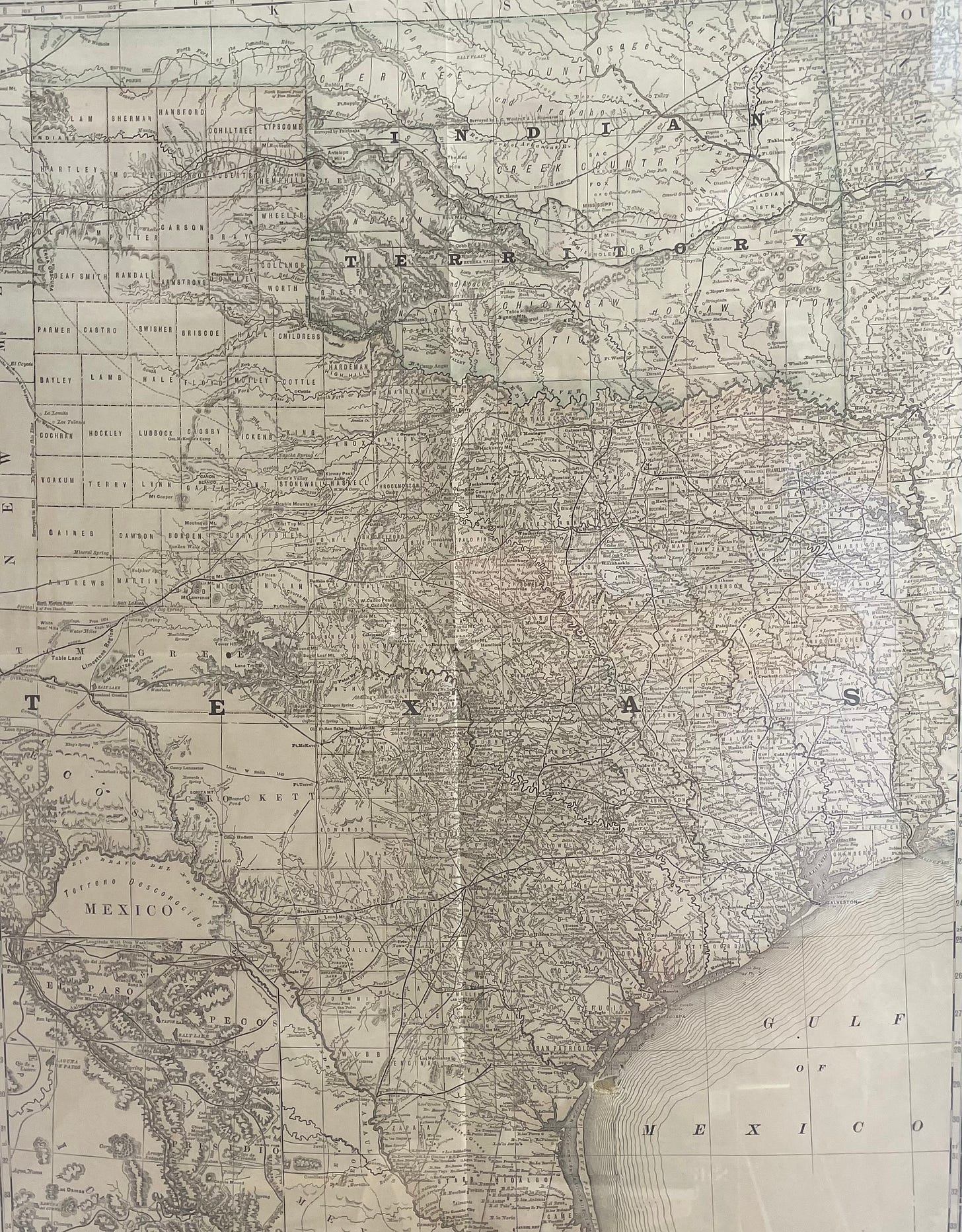

"Have you ever been out to Fort Davis? They have a great bookstore. That's where I got my book on...oh what's his name...ya know...the Apache outlaw. Geronimo, that's it. We were in that bookstore forever, and I finally came up to the register with five books. And the guy there says 'I'm gonna give you the teacher's discount: And I asked 'how'd ya know I'm a teacher?' And he said, ‘I could just tell?’ Isn't that something? He just knew."

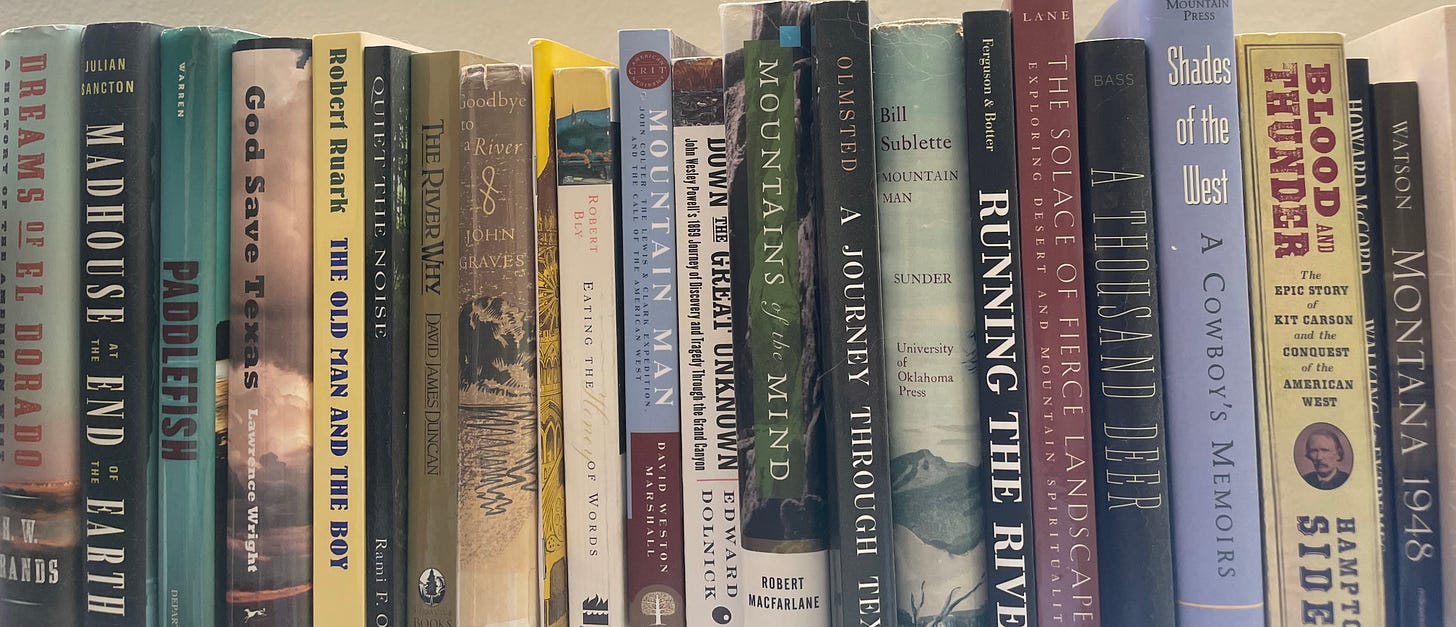

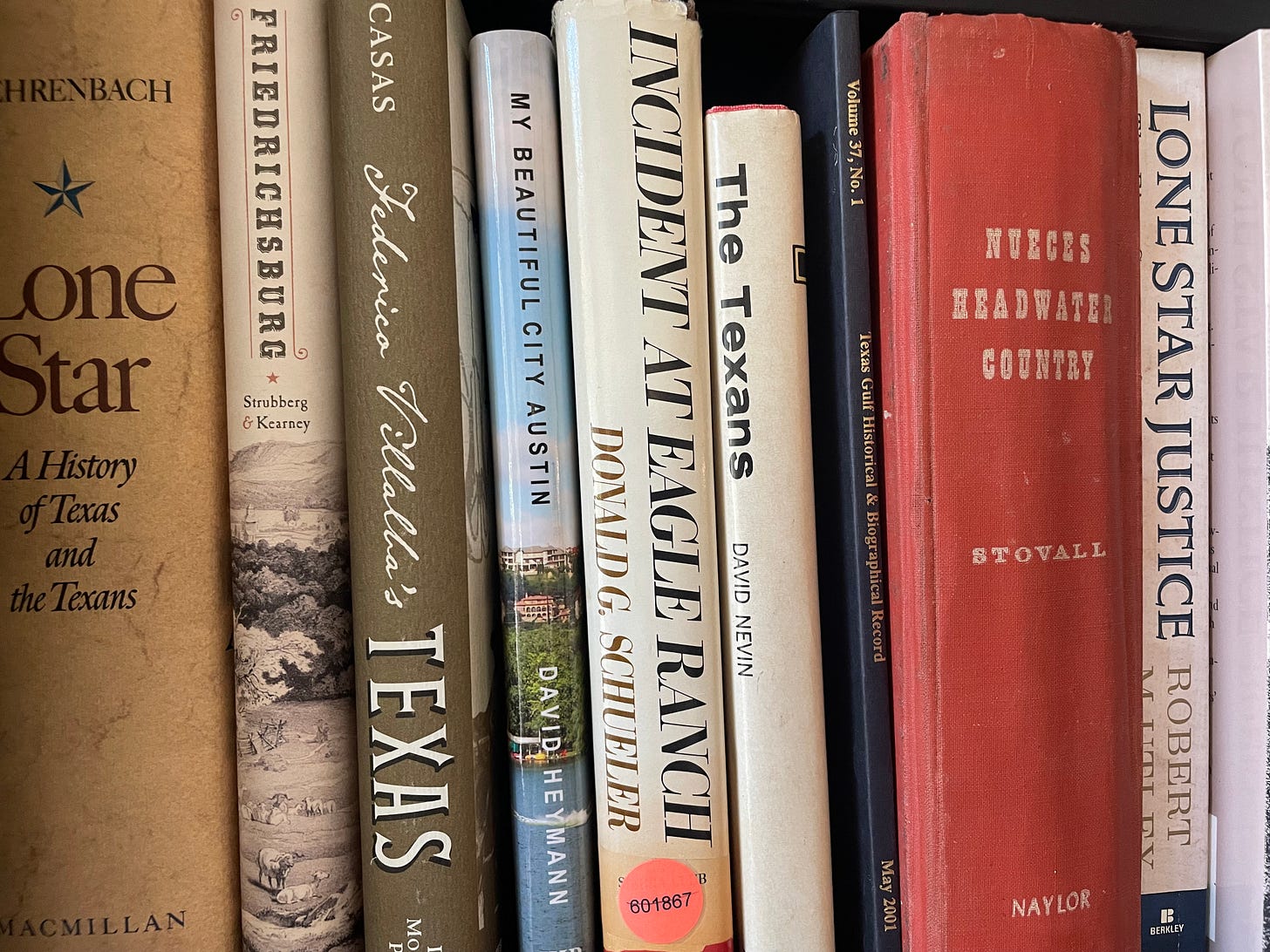

Mitch and I got going, talking about books we had both read, winding our way through the history of the American West. We talked SC Gwynne and Quanah Parker, Hampton Sides' Blood and Thunder. We journeyed with Olmsted through Texas, and traced our history through Ferenbach's Lone Star and Mann's 1493. We couldn't help ourselves. It's rare you find such a fellow literary adventurer. Every now and then as we talked, Mitch struggled to complete a thought. He couldn’t remember an author or a detail and it drove him crazy. "My chemo brain is acting up.”

He showed me that the hospital volunteer had brought him some Malcolm Gladwell and Cooking Your Way Through Cancer, but we didn't let those titles derail us long. We were soon heading back West. I told him about my current reading adventure, Son of the Morning Star, Evan Connell's epic and overwhelming masterpiece on Custer's last stand. How the great and maddening thing about the book is that Connell chases every single historical rabbit trail to its end, making each paragraph a complete side story unto itself until you fully lose the overall narrative entirely.

“Did you know Americans on the East Coast couldn't believe that Sitting Bull was really a Native American?" Those damning details fascinated me. "They thought only a West Point-trained officer could have possibly taken down Custer. There was even this West Point grad from the 1840s nicknamed 'Bison' that had disappeared out West. They thought this missing white guy, Bison, must be Sitting Bull!"

Mitch knew well the troubled history of race relations in the West. Through his teaching and community work at the Jewish Family Life Center, he had long championed social causes locally. Mitch then pulled from his stack Eric Foner's The Fiery Trial, a dense scholarly volume that chronicles Lincoln's relationship to slavery from his early days in Illinois through the Emancipation Proclamation. "This is my book from home, Adrienne brought it up. Its not the easiest read, but it's really interesting. It may take a while, but I'll get through it.

"You know, when I moved to Texas, and when I was in Pueblo Colorado—those are big hunting places. I never did get into hunting—but ya know, hunters will get their trophies mounted and put them on the wall. Certain books, like this one, are like that for me. I like to mount them up on the wall like a trophy when I'm done with them."

We smiled and laughed, and a half hour had quickly passed. I could've stayed all night, but I felt I should leave to let him get some rest. I had a long weekend off, but I'd be by next week to see him if he was still in the hospital. "When they let me outta here, well have to get together for cawffee."

I thought of Mitch often as I unwound with my family on the back porch that weekend. And every little bit of Little Bighorn trivia I read in my Custer book was something I looked forward to sharing with him. When the workweek arrived, I put Custer in my backpack and drove to the hospital early before my first shift back. It was Tuesday afternoon, time to talk with Mitch about Crazy Horse and the hubris of the Army of the West.

As I excitedly approached his room, a nervous young nurse hovered near his door. She looked fresh out of school in her blue scrubs and glasses, and seemed somewhat lost. I could tell she wasn't sure what to make of me, an ER doctor in green scrubs looking out of place on the 6 Floor. She edged over between me and the door, blocking me from going in, and asked who I was. "I'm the ER doctor who took care of Mitch when he came in. I'm just coming by to visit."

"Oh, OK" She paused, looking for words. "I'm sorry…he died…five minutes ago." My head fell forward, my lungs emptied, and my shoulders sank.

Mitch had taken a turn for the worse and stopped talking Monday afternoon. He had become more or less unresponsive, and his family had decided to focus on keeping him comfortable. I noticed the laminated photo of a green leaf clipped to Mitch's door, our hospital's secret signal that a patient is on “comfort care” and nearing the end of life. He hadn’t lived long after that. “Well, I'll just go talk to the family." I took a deep breath as the nurse moved aside.

A quiet knock, and I hesitantly walked in. And there he was in repose, pale and still, family sitting at his side. I introduced myself and asked permission to join them. The awkwardness eased a little when I found out Mitch had mentioned me to Adrienne. I told them how much I enjoyed getting to know Mitch in the very short time I knew him. I took Custer out of my bag to show them and told his family all the things I had hoped to tell Mitch. They told me a few stories about him, and how they were relieved that he wasn't suffering anymore. All the while his body lay there cold and peaceful and stiffening, eyes looking to heaven.

I wanted to get closer to Mitch in that moment, to go to the bedside, hold his cold hand and say goodbye, but that somehow felt intrusive in the moment. I didn't know if the family had even done that yet. They were still in shock that he was gone so suddenly, and didn't know what to do next. "I’ve got to figure out how to hold a Jewish funeral,” Adrienne confessed. "Mitch wrote down some prayers that he liked, but I'm Catholic. I don't know what to do.”

I offered my condolences, and told them I'd keep them in my prayers, but had to go start my shift. I asked the young nurse to call the chaplain for the family. Down the elevator and into the chaos I stepped once again, thinking about Mitch’s peaceful last stand and how his fiery trial with cancer was over at last.

Three months later I got a text from Adrienne. I must have given her my number in the room after Mitch died. We got together coffee and blueberry muffins overlooking the lake, and she was lovely. She told me all about Mitch, their 42 years together, her childhood in Austin, and how she had hated the wind in springtime in Pueblo, Colorado. Smiles turned to tears and then to gentle laughter. She could tell why Mitch liked me, she said, and that he and I would have been friends. Just before we left, she reached into her bag and handed me Mitch's copy of The Fiery Trial, his bookmark still at page 60. "Mitch was reading this when he died. He didn't get very far. I think he'd want you to have it:"

I've not gotten far in the book, but I've held it often, creasing its red spine as I flip through its pages, hearing them flap back and forth past Mitch's bookmark. I think often of the unspoken lessons Mitch taught me in his final few days. Remember to slow down, dawcta, and find common ground. Treat your patients more like people and less like cases to get through. Let your patients tell their stories and speak life back into you. That’s what'll keep you going when it gets hard. I took these lessons to heart on my ER shifts going forward, focusing much more on moments of human connection that I had before. I even undertook a year-long fellowship studying hospice and palliative medicine, connecting with my patients and their families like never before. I hope the professor knows the impact he had on his last pupil.

I do still owe Mitch a favor, though—I’ll finish The Fiery Trial for him, and I’ll mount it on my wall next to Custer.

*This story was published with Adrienne’s permission.

*The top photo is of a painting is John Moyers’ “Positive/Negative” on display at Woolaroc Museum, Oklahoma. All photos by me.

Tell me, Crash Cart Campfire friends:

When has a short-lived friendship or a “chance” encounter had a profound impact on you?

What types of books get you going?

Tommy's sister here. Beautiful story about Mitch. Recently, one of the shuttle bus drivers at MDa made a memorable impression... 1) there was a sign at the front of the bus that said "NEVER GIVE UP" and 2) she was SUPER patient while we helped my mom into the shuttle and asked me and Tommy, "is that your mommy?... y'all are good kids, which is a sign that she's a good mommy"

She indeed is.

Beautiful heartfelt story, Tyler!